‘Migration isn’t going to stop’: Salvadorans join new caravans

San Salvador – Alex Gonzalez decided to flee El Salvador at the last minute. Waking up from nightmares of being chased and killed reflecting his real-life fears of becoming a victim of gang violence, he packed a small bag and left home the same day to join the latest caravan of migrants and refugees headed north from Central America.

The 22-year-old from the department of La Paz managed to dodge pressure to join the street gang that controls his neighbourhood when he was younger, but now the gang terrorises him with extortion payments he cannot afford.

To escape escalating threats, he joined some 200 people departing the capital city San Salvador on Wednesday morning. The caravan follows on the heels of thousands of Hondurans who began to make their way towards Guatemala earlier this week.

“We are leaving a lot behind,” Gonzalez, travelling with his 20-year-old brother Jose told Al Jazeera. Leaning against a Spiderman backpack filled with a handful of clothes, Gonzalez pulled out his phone to show photos of his six-month-old daughter, Ashley Elisabeth.

Unlike his brother Jose, who has been unemployed for three months, Gonzalez gets regular work performing as a clown at special events. But he says extortion and threats have become unbearable. He makes about $230 per month, roughly on par with El Salvador’s minimum wage, but the Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13 gang forces him to hand over $150 of his earnings and harasses him with menacing phone calls when he fails to pay up.

“I would regret becoming yet another victim in El Salvador,” he says. He tried to keep a low profile as he left his neighbourhood, fearing gang member would kill him if they knew he was trying to flee. He doubts the $150 he scraped together will last him until he makes it to the US border, but he tries not worry about it, simply saying, “God is great.”

He plans to request asylum in the United States, where his 17-year-old sister is also an asylum seeker. She fled their home about two years ago, fearing for her safety after she was raped by presumed gang members. He now worries about the rest of his family, especially his daughter, and thinks she will be safer if she too leaves the country in the future.

|

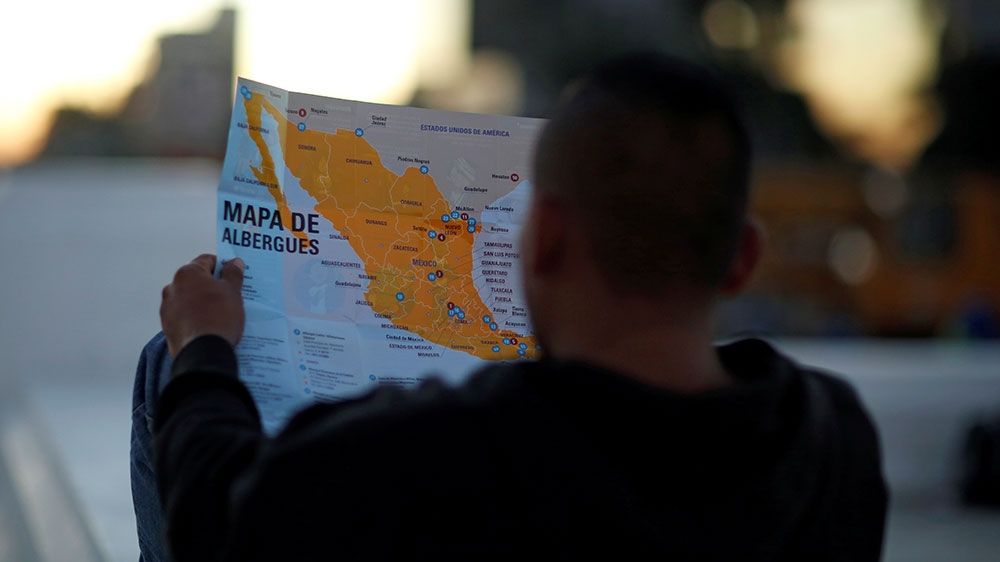

| A man holds a map as he waits to leave with a new caravan of migrants, set to head to the United States, at El Salvador del Mundo Square in San Salvado [Jose Cabezas/Reuters] |

But unlike Gonzalez, 48-year-old Rafael Guillen, from San Martin, wants his three children to have opportunities to stay in El Salvador and get a good education. He sees life in the US as a temporary plan to save up more money than he earns as a street vendor in El Salvador. He hasn’t suffered direct threats, but going from bus to bus selling sweets and cookies, he constantly has to think about avoiding crossing into rival gang turf to stay safe.

“If you leave your house (in El Salvador), you run the risk of not returning,” he told Al Jazeera. “If you migrate to another country, at least if something happens you die in the attempt.”

Like others, Guillen is undeterred by US President Donald Trump’s ongoing hostility towards Central American migrants and refugees. “As long as there is poverty, migration is not going to stop,” he says. “Not matter how tall the wall may be.”

‘If I come back, it’ll be to die’

The caravan is the fifth to leave El Salvador since last October. The majority of participants cite lack of economic opportunities and insecurity as reasons for leaving, and many hope to find safety in numbers by travelling in large groups while saving the thousands of dollars it costs to make the journey with a smuggler, according to surveys conducted by the International Organization for Migration.

Some hope to stay and work in Mexico, while others plan on joining the thousands of Central Americans already at the US border awaiting their turn to apply for asylum.

Government statistics based on interviews with deportees point to economic factors as the overwhelming driver of immigration from the country, followed by insecurity and family reunification. But rights groups point out causes of migration are often not clear cut and that a lack of government support for victims of violence has contributed to an upswing in the number of Salvadorans seeking asylum in the US and other countries in recent years.

The UN refugee agency UNHCR reports 49,726 Salvadorans requested asylum in the United States in 2017, a more than eightfold increase from 2013. Salvadoran asylum requests in Mexico and Costa Rica are also on the rise.

If you leave your house (in El Salvador), you run the risk of not returning. If you migrate to another country, at least if something happens you die in the attempt.

Rafael Guillen, caravan participant

Jose Martin, from San Luis Talpa, hopes to make the case for asylum in the US. The 18-year-old, who identifies as trans, says discrimination against the LGBT community makes it difficult to find work. And threats of violence are a constant.

“I’m going to see if I can request asylum and not get deported, because if it come back, it’ll be to die,” says Martin, who had a trans friend was murdered two years ago.

As one of the most violent countries in the world over the past decade, El Salvador’s rate of people driven from their homes due to violence and conflict – 3,600 out of every 100,000 inhabitants -is second only to Syria, according to the International Displacement Monitoring Center [pdf]. Tough-on-crime policies to a crackdown on violent gangs have failed to improve security over the past 15 years.

A total of 235,708 people were forced to move in 2018 to escape threats or violence in the country of 6.3 million, and six out of 10 internally displaced people have considered leaving the country, more than half of them with eyes set of the United States, surveys by the University Institute of Public Opinion at the José Simeón Cañas Central American University in San Salvador found.

Climate change also increasingly drives migration from parts of El Salvador along Central America’s drought-prone Dry Corridor, which also stretches across Honduras and Guatemala, as farmers suffer crops losses amid years of intensifying droughts.

Regional leaders meet

Of some 2,700 Salvadorans that left the country in four caravans late last year, nearly 600 returned home, Aquiles Magana, head of El Salvador’s National Council for the Protection and Development of Migrants and Their Families, told Al Jazeera.

Magana said the government seeks to educate people about potential dangers on the migrant trail, especially for young children, to make them think twice about joining the caravan, but few change their minds. “If they decide to go, we can’t stop them,” he said.

“What good is it for the government to try to stop us if it isn’t giving us any [support]?” said 23-year-old Abigail Perez as Wednesday’s group began their journey north. Travelling with her partner, Franklin, and their two-year-old daughter, Perez hopes of save money in Mexico before the family heads to the United States.

The caravan departed after government officials from the El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico met in San Salvador on Tuesday to discuss a regional development plan aimed at stemming migration through job creation and improvements in security in the Northern Triangle and southern Mexico.

|

| Salvadorans take part in a new caravan of migrants and refugees, set to head to the United States, as they leave San Salvador, El Salvador [Jose Cabezas/Reuters] |

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has called for an investment of $30bn to support a so-called Marshall Plan for Central America. Critics argue the strategy, which so far includes no significant new investment from the United States, is likely to favour militarised security initiatives and private investment schemes that historically have failed to improve the living conditions in the region.

Ursula Roldan, director of the Institute for Research and Social Projection on Global and Territorial Dynamics at the Rafael Landivar University in Guatemala City, told Al Jazeera she is “alarmed” that mass migration continues amid uncertainty over how immigration authorities will receive the caravans, including in Guatemala, currently pitched in constitutional crisis.

“I didn’t think the caravans would be replicated this much, because the results haven’t been as positive as we would hope,” Roldan said. “But we are seeing that people prefer to go in caravans because they feel more protected.”