Inside Skopje, Europe’s most polluted capital city

Skopje, North Macedonia – Every winter, the pollution in Skopje skyrockets to alarmingly high rates. In 2018, Skopje became the most polluted capital city in Europe reaching the highest annual mean of PM 2.5, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Tiny particles named for their diameter of 2.5 micrometres – about three percent of the diameter of a human hair – PM 2.5 are considered the most dangerous air pollutants for health.

They are small enough to penetrate the respiratory system and even the bloodstream and have been linked to premature deaths and various diseases.

“By breathing this air, we are slowly dying,” Tomislav Maksimovski, a Skopje resident, told Al Jazeera.

“We feel the pollution. You can feel it in your mouth and lungs. Our children are suffering and our parents are coughing. We don’t deserve to live in such a polluted city.”

Skopje, in the centre of the Balkan Peninsula, is nestled in a valley between mountain ranges that hem the city in from the north and the south. This landscape proves deadly in the winter.

As warm air rises up from the mountains, it meets the colder, heavier air travelling downwards. This temperature inversion creates a blanket of smog that settles heavily over the valley, trapping polluted air on the city streets and in the lungs of the residents.

|

| Several factories operate in Skopje, many of which burn coal and other non-ecological sources of fuel. [Joi Lee/Al Jazeera] |

“Some of the pollution problems specific to the western Balkans may be due to industries, in general older than in the rest of Europe, as well as domestic heating,” said Alberto Gonzalez Ortiz, an air quality expert from the European Environment Agency (EEA).

“For instance, the use of coal implies that the PM emissions are high. The vehicles may also be older than in other parts of Western Europe.”

Many of the power plants and small factories in North Macedonia exist from the communist-era, before the 1990s, and burn brown coal (lignite) which is cheap, abundant but highly polluting.

A 2016 study by the Health and Environment Alliance found that within areas of former Yugoslav countries, 16 lignite plants emit as much pollution as all of the European Union’s 296 power plants combined.

The loosely regulated fleet of old vehicles that crowd Skopje is also highly polluting.

Many of those came by way of the EU when the previous VMRO-DPMNE government in the country allowed the import of old vehicles in 2010.

Many of these were running on diesel and no longer met EU environmental standards.

|

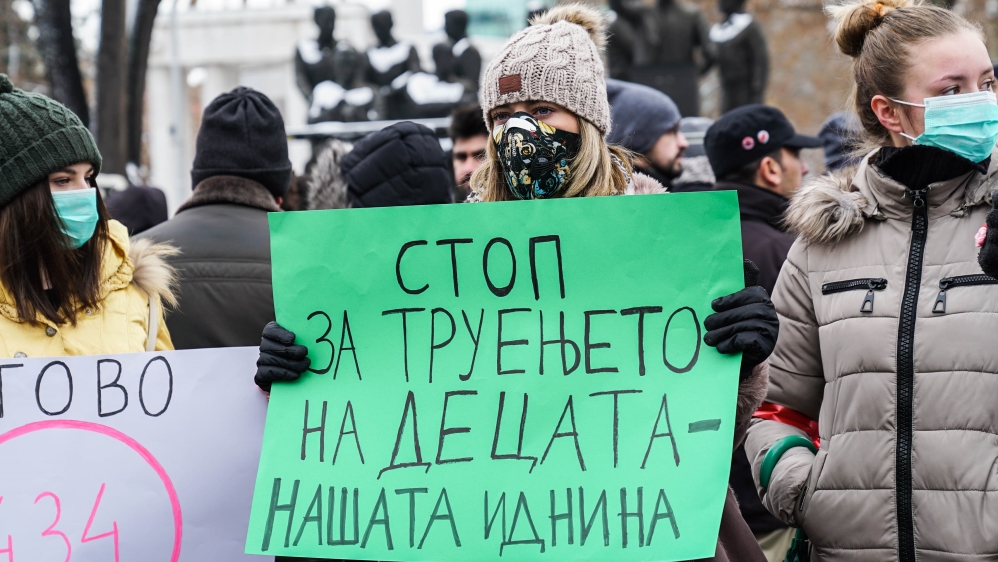

| ‘Stop poisoning our only children,’ reads a banner at a protest in Skopje [Joi Lee/Al Jazeera] |

But one of the biggest contributors to pollution are the combustion processes, at 77 percent, which includes household heating.

“Another reason for the pollution is that too many citizens, because of their financial situation, use firewood for heating,” said Jani Makraduli, North Macedonia’s deputy minister of environment.

Although the country’s electricity tariffs, alongside Serbia, are among the lowest in Europe, energy can cost up to a third, or even a half, of the average monthly salary, especially during winter.

Most residents cannot afford clean energy heating sources, and as many as 42 to 45 percent of the city’s residents turn to firewood to heat their homes.

A lot of those are purchased on the black market – cheaper but more toxic to the environment.

Heart diseases and strokes account for 80 percent of the premature deaths associated with air pollution, with lung diseases and lung cancer in tow, as well as other respiratory cardiovascular disease and cancer.

“Some of the more serious complications from polluted air are the carcinogenesis,” said Nikola Brznov, a doctor who works in the emergency department at Mother Teresa University Hospital in Skopje.

Younger generation at risk

Air pollution is also linked to negative health impacts on newborns and children, including on neural development and cognitive capacities that can lower performance and quality of life as the child grows older.

“After long-term exposure to polluted air, our organs start to manifest that in some chronic illness, mainly respiratory diseases and heart diseases. In the long run, I think the younger generation will be affected,” added Brznov.

With more studies explaining the link between pollution and health, as well as air monitoring apps like MojVozduh (MyAir) that draw data from over 40 measuring stations in Macedonia, citizens are more educated about the scale and effect of pollution.

However, concerns still exist in huge numbers, including those of parents across the city who are worried for their children’s futures.

In 10 years, our health and that of our children will deteriorate significantly

Tomislav Maksimovski, Skopje resident

“I am afraid of the pollution and I am concerned for my kids,” said Ivana Georgievska, a mother of three. “That’s why we try to use our free time to go out of the city for fresh air, either on Vodno mountain or in the village.”

Maksimovski, who has one child, said in “10 years, our health and that of our children will deteriorate significantly.”

Late last year, the government announced, for the first time, a strategy towards combating pollution, aiming to halve it in Skopje over the next two years.

Some key factors include encouraging and supporting residents to move from fuel-burning heating to more ecological sources like gas or central heating.

However, many residents are doubting the government is making an appropriate investment, having set aside only a small annual budget of 1.6 million euros ($1.8m), which experts say is not enough.

“We are not seeing that the government is fighting pollution,” said Davor Vrgovikj who is part of the Cancerogenous Society which organises weekly protests in Skopje.

“Our main demand is for more funds to be allocated. We don’t care what political party it is. We don’t ask for medals. We just want clean air.”

|

| Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia, seen through a hazy layer of smog [Joi Lee/Al Jazeera] |