Hong Kong sees new umbrella protests over China extradition bill

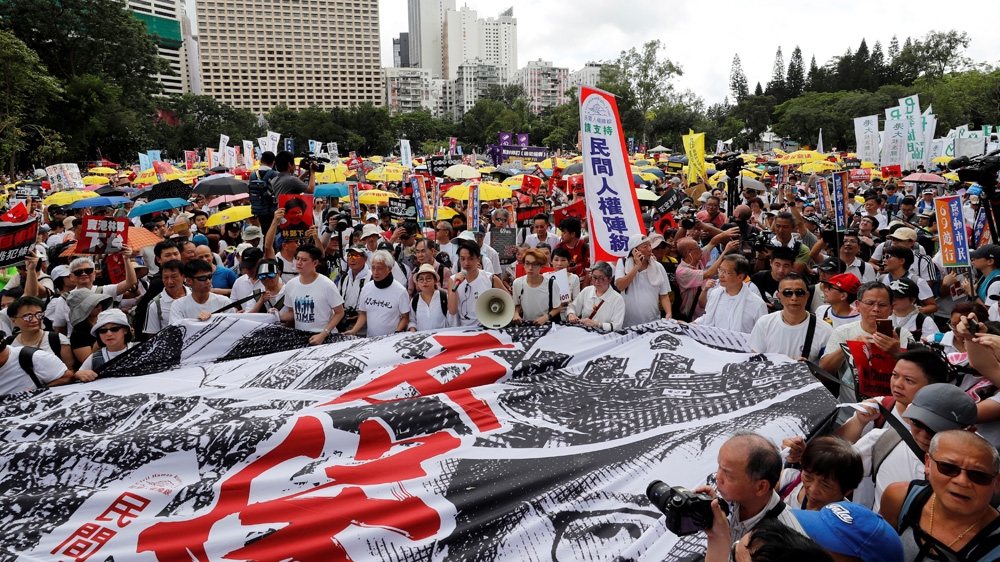

Hundreds of thousands of people have marched through Hong Kong in the last bid to block a proposed extradition law that would allow suspects to be sent to China to face trial.

Police chiefs called for public restraint, government-funded broadcaster RTHK reported on Sunday, as they mobilised more than 2,000 officers for the mass march.

After seven hours of marching, organisers estimated 1,030,000 people took part, far outstripping a demonstration in 2003 when half that number hit the streets to successfully challenge government plans for tighter national security laws.

That would make it the biggest rally in three decades, second only to a demonstration in 1989 that drew 1.5 million people to support the Tiananmen Square protests in China, according to organiser Civil Human Rights Front who put Sunday’s participation at 1.03 million.

A police spokesman however said police estimated 240,000 were on the march “at its peak”.

Hong Kong’s leader, Carrie Lam, has pushed forward with the legislation despite widespread criticism from human rights and business groups.

Opponents say that China’s legal system would not guarantee the same rights to defendants as in semi-autonomous Hong Kong.

Protesters believe the proposed law before Hong Kong’s semi-democratic Legislative Council would damage the city’s rule of law and put many at risk of extradition to China for political crimes.

Protesters who arrived chanted “no China extradition, no evil law” while others called for Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam to step down. One protester held a sign reading “Carry off Carrie.”

Lam has tweaked the proposals but has refused to withdraw the bill, saying it is vital to plug a long-standing “loophole”.

However, people remain suspicious and question the fairness and transparency of the Chinese court system.

“[Lam] has to withdraw the bill and resign,” veteran Democratic Party lawmaker James To told crowds gathering outside the city’s parliament and government headquarters in the Admiralty business district on Sunday night.

“The whole of Hong Kong is against her.”

After To spoke, thousands were still arriving, having started the march five hours earlier, filling four lanes of a major thoroughfare.

A sea of protesters chanting slogans and demanding security chief John Lee to step down as they are stucked in Leighton Road in Causeway Bay #extraditionbill @SCMPNews pic.twitter.com/hB32PHkm2P

— Jeffie Lam (@jeffielam) June 9, 2019

The crowd on Sunday included young families pushing babies in prams as well as the elderly braving 32 degrees Celsius heat.

“Nobody trusts the mainland government, how can people feel they would get a fair trial in the mainland,” Claudia Mo, a legislative councillor in Hong Kong, told Al Jazeera.

“There is no due process there, and it means that people can just be whisked away across the border to face a biased court system.”

Al Jazeera’s Sarah Clark reporting from Hong Kong said the initial expectation of around 300,000 people joining the rally has been beaten.

“Where the rally started at Victoria Park it was full and overflowing… we’ve seen people of all generations – pro-democracy activists, student union groups, and families who are joining this rally, united in their opposition to this extradition bill,” Clark said.

“But despite their efforts, this bill is likely to be passed. The Hong Kong government has the majority in the city’s parliament and the chief executive Carrie Lam wants a vote by the end of the month.”

Yellow umbrellas

Demonstrators carried yellow umbrellas, which became the symbol of passive resistance during protests in 2014, when residents demanded more transparent elections from China.

Opposition to the proposed bill has united a broad range of the community, from usually pro-establishment business people and lawyers to students, pro-democracy figures and religious groups.

“I come here to fight,” said a wheelchair-bound, 78-year-old man surnamed Lai, who was among the first to arrive at Victoria Park.

“It may be useless, no matter how many people are here. We have not enough power to resist as Hong Kong government is supported by the mainland,” said Lai, who suffers from Parkinson’s disease.

“I think it’s the worst law ever,” said Hera Poon, who brought her entire family to the rally. “We all understand that China is rocking the justice system in Hong Kong.”

Poon expressed concerned with China’s 99-per-cent conviction rate, compared to Hong Kong’s strong rule of law, and that extradition might be used to prosecute political prisoners. “If the government aren’t happy with you they will charge you and make you guilty,” she said.

The marchers slowly made their way through the crowded Causeway Bay and Wanchai shopping and residential districts to Hong Kong’s parliament, where debates will start on Wednesday into government amendments to the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance. The bill could be passed into law by the end of June.

The changes will simplify case-by-case arrangements to allow the extradition of wanted suspects to countries, including mainland China, Macau and Taiwan, beyond the 20 that Hong Kong already has extradition treaties with.

But it is the prospect of renditions to mainland China that has alarmed many in Hong Kong.

The former British colony was handed back to Chinese rule in 1997 amid guarantees of autonomy and freedoms, including a separate legal system.

“It’s a proposal, or a set of proposals, which strike a terrible blow … against the rule of law, against Hong Kong’s stability and security, against Hong Kong’s position as a great international trading hub,” the territory’s last British Governor, Chris Patten, said on Thursday.

Foreign governments have also expressed concern, warning of the effect on Hong Kong’s reputation as an international financial hub, and noting that foreigners wanted in China risk getting ensnared in Hong Kong.

The concerns were highlighted on Saturday with news that a local high court judge had been reprimanded by the chief justice after his signature appeared on a public petition against the bill.

Human rights groups have repeatedly expressed concerns about the use of torture, arbitrary detentions, forced confessions and problems accessing lawyers.

Hong Kong government officials have repeatedly defended the plans, even as they raised the threshold of extraditable offences to crimes carrying penalties of seven years or more.

They say the laws carry adequate safeguards, including the protection of independent local judges who will hear cases before any approval by the Hong Kong chief executive.