Coerced to confess: How US police get confessions

Why would someone confess to a crime they did not commit?

While the idea may seem inconceivable to many, more than 12 percent of all overturned wrongful convictions in the United States in the past 30 years have involved a false confession, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations.

Psychologists have been researching this issue for decades, and some say that common interrogation tactics used by police can be a contributing factor.

The Reid Technique, introduced in 1962 by polygraph expert John Reid and law professor Fred Inbau, is a confrontational tactic that involves accusing the suspect of a crime. It claims to have an 85 to 90 percent success rate.

It is one of the most widely used methods in law enforcement, and also one of the most widely criticised for producing false confessions, although its developer John E Reid and Associates says the technique has checks in place to prevent false confessions.

It is legal in the US for police to lie about evidence and coercive interrogation techniques are often used, sometimes subjecting suspects to hours of verbal abuse, intimidation or conditions that are mentally and physically exhausting, resulting in the suspect seeing a confession as their only way out of the situation.

Advocates say false confessions can be curbed through simple measures like recording interrogations or warning a jury that a suspect may have been coerced.

Some states have taken preventive steps; almost half of US states require recording certain custodial interrogations, and in 2017 a major police consulting firm announced it would no longer teach the Reid Technique.

Still, the problem persists. Here is a look at six cases in which police coerced confessions from suspects – whether they were guilty or not.

The Central Park Five

|

| Kevin Richardson, one of the wrongly convicted Central Park Five, in June 2014 [Carlo Allegri/Reuters] |

One of the most famous examples of coerced confessions involved a group of five black and Hispanic teenagers who were interrogated for the beating and rape of a white woman who was jogging in New York City’s Central Park in 1989.

The boys were between 14 and 16 years old and were being held as suspects for another series of attacks that took place that night.

All five confessed to the crime after being interrogated for hours without lawyers, and according to them deprived of food and sleep. They were convicted despite giving accounts that were inconsistent with each other and the crime scene and no supporting DNA evidence.

Four of the teenagers – Yusef Salaam, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray and Raymond Santana – each spent about seven years in prison while the fifth, Korey Wise, spent 13 years behind bars.

In 2002, a man who was serving a life sentence for raping several women and murdering one, came forward confessing to the crime and DNA evidence was later matched to his. The five men were exonerated and in 2014 they reached a $41m settlement with the city.

Andrew and Jackie Wilson

Chicago is considered the “false confessions capital” of the US. More than 30 percent of exonerations involving false confessions have come from Illinois state, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

Andrew and Jackie Wilson were interrogated by police commander Jon Burge and his team for the shooting of two police officers in Chicago in 1982. Andrew said he was beaten, suffocated, burned against a radiator, and electrocuted on his face and genitals.

They confessed and the two Wilson brothers were found guilty in court. Andrew died in prison, while Jackie was released in 2018 after spending 36 years in jail when a judge ruled that his confession was coerced.

The injuries Andrew sustained – later reported by a medical official – helped expose Burge’s operations. Burge was accused of torturing more than 100 people, most of whom were black, between 1972 and 1991, using techniques that included suffocating suspects with plastic bags and holding individuals at gunpoint.

Tens of millions of dollars were eventually paid in settlements to Burge survivors. In 2015, the city of Chicago paid reparations and required public schools to teach students about the Burge cases.

About 20 people tortured by Burge and his team are still in prison, according to Chicago Torture Justice Memorials.

|

| US police are allowed to lie to and manipulate suspects into confessing to a crime [Jawahir al-Naimi/Al Jazeera] |

Nga Truong

In 2008, 16-year-old Nga Truong confessed to killing her 13-months-old son in Massachusetts. The American-Vietnamese teenager had phoned emergency services after her baby had stopped breathing, and one-and-a-half hours later a doctor pronounced him dead.

The policemen who questioned Truong in a confined room made accusatory statements, lied about evidence and offered false promises.

In a video of the confession, obtained by American public radio station WBUR, the police said that Truong would be given a more lenient punishment if she confessed, and that her and her brothers could be put into a better living situation. At the time she lived in an apartment with her boyfriend, mother, and siblings.

The police also referenced an incident when Truong was eight years old and her mother had left her to look after her baby brother, who died from sudden infant death syndrome under her watch.

A judge watched the tape and ruled that the confession was coerced and Truong was released – after almost three years in jail.

Henry McCollum and Leon Brown

Henry McCollum and his half-brother, Leon Brown, were convicted in 1984 for the rape and murder of an 11-year-old girl in North Carolina after both teenagers confessed to the crime. They were 19 and 15 at the time and both had intellectual disabilities.

Both soon recanted, saying they were coerced, but to no avail. Brown was eventually sentenced to life in prison, while McCollum spent 30 years on death row.

They were exonerated on DNA evidence in 2014 and later given pardons of innocence. The state of North Carolina paid $750,000 compensation to both of them in 2015.

About 70 percent of people who falsely confessed and were exonerated have mental illnesses or intellectual disabilities, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

One US Supreme Court justice cited the McCollum case to argue against the death penalty, saying it is unconstitutional because wrongful convictions are inevitable.

|

|

In the past 25-plus years, there have been 248 recorded exonerations involving false confessions, according to data from The National Registry of Exonerations [Jawahir al-Naimi/Al Jazeera] |

The Norfolk Four

Four sailors aged between 20 and 27 were accused of the 1997 rape and murder of an 18-year-old woman in Norfolk, Virginia. They were subjected to hours of questioning and were threatened with the death penalty.

Their DNA did not match with crime scene evidence, and the men’s confessions contradicted the details of the crime and each other’s accounts.

Around the time of their conviction, a DNA analysis found a match with a man serving time in prison for other crimes, and in 2000 he pleaded guilty.

Still, all four sailors were convicted and spent years in prison. In 2009, three of them – Danial Williams, Derek Tice, and Joseph Dick Jr – were given conditional pardons that left them still registered as sex offenders, and were released.

The fourth, Eric Wilson, who had only been convicted for rape, had already served his full sentence. The following years the men were each exonerated and in 2017 they were fully pardoned by the state.

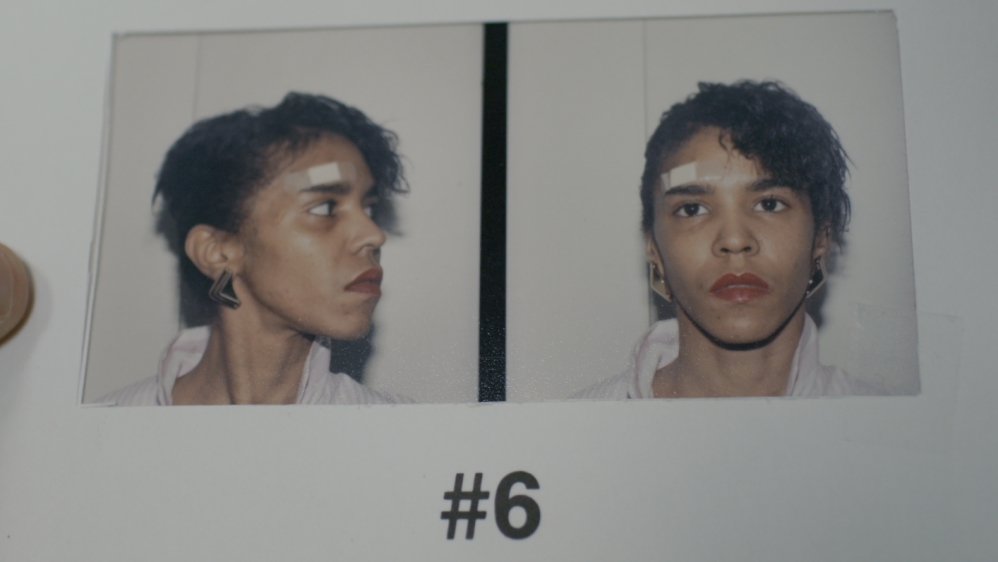

Renay Lynch

|

| Renay Lynch has spent more than 20 years in prison for a crime she says she didn’t commit [Screengrab/Al Jazeera] |

False confessions can take years to prove, leaving many to argue for their innocence from behind bars.

In 1995, Renay Lynch confessed to being an accomplice in the murder of her landlord in Amherst, New York, but later said the confession was false. Her lawyers stated she was addicted to drugs at the time and was coerced by police.

A “jailhouse informant” – or prisoner that testifies against someone for perceived benefit or reward – also said that she had been an accomplice. In 1998, she was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison where she remains until now.

“I believe her confession is kind of nonsense. There’s inconsistencies between the physical evidence and what she says … If they [the police] knew that Kareem Walker was in Florida at the time of the crime, then Renay’s confession can’t possibly be true, because she’s confessing to going to rob the landlord with Kareem. Had the defence been able to put that on, her confession would have made no sense. But the defence was never told,” says defence attorney Jane Fisher-Byrialsen.

“Our goal is to get Renay out of prison, but that can take a really long time.”

Last year, a judge permitted the retesting of DNA evidence from the crime scene which attorneys say could help prove her innocence. She has been in prison for more than 20 years.