1983 Beirut barracks bombing, through the lens of a camera

Early morning on Sunday, October 23, 1983, Pierre Sabbagh awoke from an uncomfortable night’s sleep in the grounds of the US Battalion Landing Team (BLT) headquarters in Beirut, Lebanon.

The Lebanese photojournalist had slept in a foxhole at the BLT’s location of the American military compound – home to the US Marines from the Multinational Peacekeeping Force (MNF) – and all was quiet. In a city that had rained bullets and bombs since Lebanon’s bloody civil war had erupted in 1975, Sabbagh gathered his belongings to explore outside the camp.

“I was sleeping in the foxhole and it wasn’t really pleasant,” recalled Sabbagh, then a 23-year-old shooter for United Press International (UPI). “And I saw there was nothing particularly happening – so I decided to leave the US base in the very early morning.”

As the marines slept soundly in their bunks – or began to rouse themselves from another unpredictable night in the restive Lebanese capital – the base at Beirut International Airport was shattered by a massive blast.

A truck laden with explosives – later estimated to be the equivalent of 12,000 pounds of TNT – had rammed the BLT after crashing through the compound’s fortified perimeter. The guards on early morning duty stood no chance as the vehicle’s driver detonated his cargo on the ground floor of the headquarters. Of the men stationed there, 241 US service personnel were crushed to death in the rubble. A second bombing at the French contingent killed 58 French peacekeepers. Another six Lebanese civilians were also killed in the twin attack.

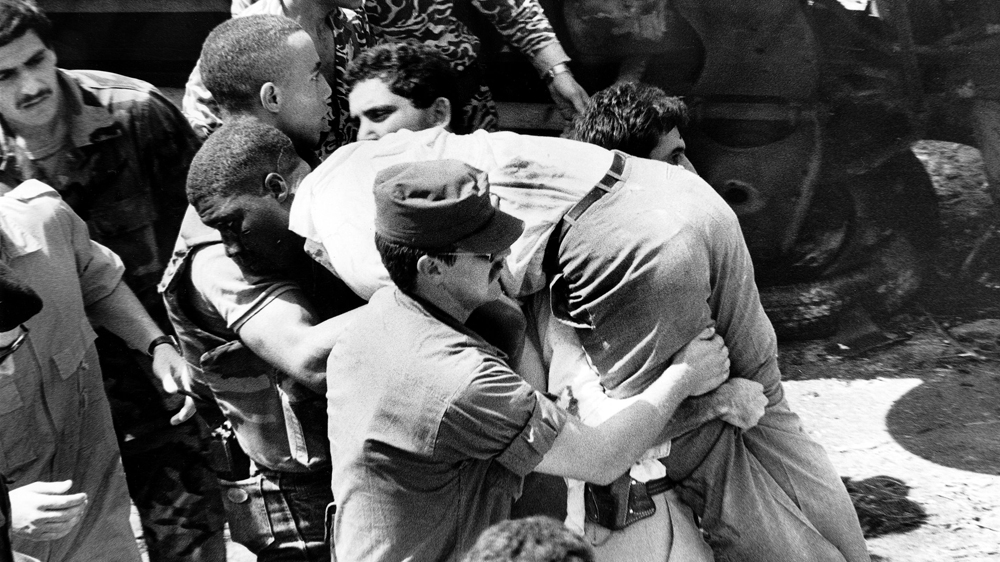

|

| Two suicide bombers detonated truck bombs at the French and US barracks [Pierre Sabbagh/Al Jazeera] |

The events of that day, 35 years ago, remain fresh in the mind of Sabbagh, who was the first photojournalist on the scene of the bombing, which took place at 6:22am.

“When I heard the blast on the road outside the base, I immediately headed back,” recalls Sabbagh, now 58, who said he had left the camp about 15-20 minutes before the explosion. “That’s how I was able to be present inside before they closed the whole site to press and photographers.”

A then little-known Iranian-backed group calling itself Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility for the bombing as it did for the deadly truck bomb attack on the French military barracks of the MNF the same morning. Many reports contend that this group would eventually grow into Hezbollah – the Lebanese Shia group backed by Iran and Syria. Decisive responsibility remains unclear to this day, however.

‘Smoke and rubble’

Speaking at length for the first time of his experience that day to Al Jazeera, Sabbagh said that when he returned to the site where he had been present minutes earlier, he was faced with “a lot of smoke, dust, dirt and rubble”.

“I rushed in and fell on the ground… and was helped up by a guard, who brought me into the secured perimeter in fact before he received the orders to close the area,” he said.

The Beirut-born Sabbagh, who describes his re-admission into the flattened compound as “pure chance”, then began shooting for over two hours as US military personnel struggled to get a grip of the grim situation. He snapped his Pentax camera almost continuously – moving from black and white film to colour and back again. Little could have prepared him for the horror in which he now found himself as a young professional photographer, but he fell back on his experience shooting the country’s complex civil war.

For a man who took up photography as a hobby at 16, and who went on to drop a hotel management degree in order to focus on his photojournalist career, the events of October 23, 1983, presented an assignment he could not have foreseen. Indeed, the bombing had taken unconventional warfare to new heights; the FBI later said the explosion was the largest conventional blast they had ever investigated.

The US itself had arrived in Beirut in August 1982. They were part of the peacekeeping force that also included a French, Italian and British military contingent that was largely unsuccessful in keeping the warring parties from decimating parts of the city. By the time of the bombing, violence between the various Muslim and Christian factions had been raging for eight long years.

However, the US’ alliance with Israel prompted Lebanon’s Muslim population to view US President Ronald Reagan’s White House as endorsers of a Christian-led Lebanese government pursuing US-Israeli interests. In September 1983, and following the suicide bombing on the US embassy in April, American involvement became deeper still when US warships, supporting Lebanese army operations, shelled Muslim positions in the Shouf Mountains.

|

| The attacks eventually played a large role in the pullout of the peacekeeping force from Lebanon [Pierre Sabbagh/Al Jazeera] |

The culmination of these events was a bombing that put Sabbagh front and centre of an international incident. He was finally removed from the blast site by US military when his cordoned-off photographic competition drew attention to his privileged position inside the destroyed remains of the military compound. He was, he explained, asked to give up his camera rolls – but after consulting with his boss, “decided to submit empty films”.

His iconic shots of that grim day were published internationally, not least in French-language news magazine, Paris Match.

He recalls the images portraying the “expressions in the eyes” of the surviving US Marines – something he said he couldn’t quite appreciate looking “through the viewfinder”. Soft-spoken and thoughtful, Sabbagh doesn’t fully elaborate on the “feelings” he felt days after the bombing – but at the end of 1984, he quit the photojournalism business. He was just about to get married and the kidnappings in Beirut made him re-think his career.

US pullout

The Americans, for their part, pulled out of Lebanon four after the bombing, in February 1984. Maurice Jr. Labelle, assistant professor of history at the University of Saskatchewan, told Al Jazeera that initially after the bombing Reagan refused to back down, instead declaring an early version of the war against “terrorism” and that US forces would stay until a “lasting peace” was forged.

“A lasting peace, in the end, did not engender a US retreat; rather, withdrawal was driven by an accumulation of political assassinations, which targeted many Americans, including American University of Beirut (AUB) president Malcolm Kerr, and [the] ensuing domestic congressional protests,” Labelle said.

“Reagan’s so-called peace mission in Lebanon was an utter failure. In fact, Reagan’s so-called peace initiative and open support for the Israeli occupation and [Israel’s] Lebanese allies set ‘peace’ and the normalisation back,” Labelle added.

|

| Born in Beirut, Sabbagh was the first photojournalist on the scene of the bombing [Nabil Ismail/ Al Jazeera] |

Today, Sabbagh, a married father-of-two, and a dual Lebanese-French citizen, manages a photographic distribution company in Beirut that deals in Nikon cameras. Though he still indulges his passion for photography in his spare time, he says he deflects frequent requests to showcase his body of work, through the likes of an exhibition, from that bloody day in October 1983.

“It’s a closed story for me,” he said.