Abdelaziz Bouteflika: Algeria’s longest serving president

A saviour for some, an opportunist for others, Algeria‘s Abdelaziz Bouteflika is no stranger to controversy.

Elected president of the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria in 1999, the 82-year-old is the fifth and longest-serving head of state the North African country has had.

He resigned on April 2, following weeks of massive street protests against his two-decade rule.

Hundreds of thousands of people took part in nationwide demonstrations demanding the ailing leader, who suffered a debilitating stroke in 2013, step down.

They said he was no longer fit to run the country and called for him and his inner circle to quit, in order to allow a real democracy to be established.

Partisans of the veteran leader credit him with ending a bloody civil war that claimed the lives of an estimated 200,000 Algerians throughout the 1990s, but his critics argue he overstayed his welcome.

War of liberation

Originally from the city of Tlemcen in Western Algeria, Bouteflika was born in the Moroccan town of Oujda on March 2, 1937.

In 1956 and at the age of 19, Bouteflika joined the Army of National Liberation (ALN), the military branch of the FLN, then waging its war of independence against colonial France.

The young Bouteflika quickly rose through party ranks, winning the trust of Houari Boumediene, an ALN commander based in Morocco who later seized power through a bloodless coup in 1965.

|

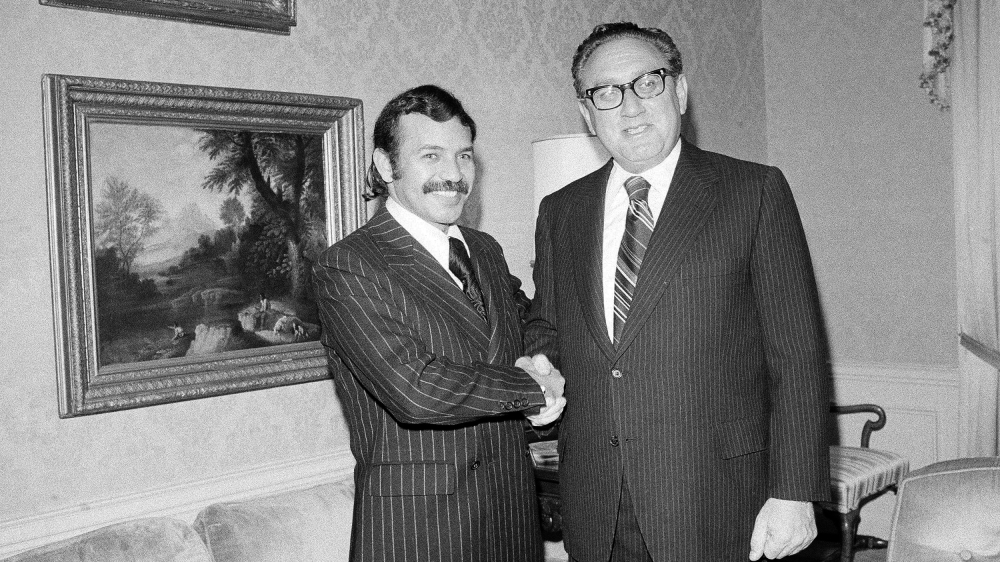

| Abdelaziz Bouteflika with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in 1975 [Dave Pickoff/AP] |

Boumediene appointed Bouteflika administrative secretary for the fifth Wilaya – Arabic for province – in 1957, effectively charging the young officer with reporting on the situation in his ancestral region.

After Algeria gained its independence in 1962, members of the ALN based in western Algeria and along the Moroccan border – known as the “Oujda group” or “clan” – assumed control of the nascent state.

Boumediene’s protege was named minister of youth, sports and tourism at the age of 25 in Algeria’s first post-independence administration under the leadership of President Ahmed Ben Bella.

In 1963, Bouteflika became the world’s youngest minister of foreign affairs – a record that he still holds to this day.

Bouteflika’s age did not take away from his important role in shaping independent Algeria’s role in world affairs.

“However, it is worth placing Bouteflika’s age in context,” said Arthur Asseraf, a historian at Cambridge University.

“Algeria at independence was a young country, led by a radical revolutionary generation that had decided to break with the past.”

“The man whom Bouteflika replaced, Khemisti, became Foreign Minister aged 32 in 1962.”

Championing third-worldism

Colonisation still weighed heavily on Algeria’s consciousness, influencing the country’s foreign policy and determination to free subjugated people around the world.

Movements ranging from Eldridge Cleaver’s Black Panther Party to the National Front for the Liberation of Oman and the Arabian Gulf found refuge in the Algerian capital.

Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara and South Africa’s Nelson Mandela also received material support and in the case of the latter, military training.

Young though he may have been, Bouteflika knew how to play his cards right in a context of rapacious intraparty rivalry.

He stuck by his mentor, Boumediene, during the putsch that overthrew Ben Bella in June 1965 and was kept on as foreign minister.

In 1967, following the Arab military defeat against Israel during the Six-Day War, Bouteflika broke diplomatic relations with the United States.

“There’s no doubt that imperialism has hit again in the Middle East,” he said.

Dressed in tailored suits and cigar in hand, Algeria’s top diplomat built a reputation as an indefatigable defender of “third-worldism”, the idea that newly liberated nations should side with neither the West nor the Soviet bloc in their Cold War rivalry.

In 1974, Bouteflika was named president of the UN General Assembly and in an unprecedented move, invited Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat to address the world governing body for the first time.

After Boumediene died in 1978, however, Bouteflika began losing his status. Corruption charges forced him into self-imposed exile in 1981, first to Switzerland and then the United Arab Emirates.

Return to Algeria

With an economy heavily dependent on hydrocarbon sales, Algeria’s ruling elite was forced to relinquish its single-party system when oil prices collapsed in the mid-1980s.

A gradual political liberalisation ensued that allowed the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) party to gain a foothold in domestic politics.

Bouteflika returned to Algeria in 1987 and was readmitted to the FLN’s central committee two years later.

The military cancelled the country’s 1991 legislative vote which historians say would have certainly brought the FIS to power in Africa’s biggest country.

|

| Bouteflika gestures broadly during a campaign speech in 1999 [Zohra Bensemra/Reuters] |

The move was not without its repercussions. Various militias were formed and subsequently waged a 10-year revolt against the state.

In 1994, amid the raging civil war, Bouteflika turned down an offer to become president, fearing the military had too much power and would have prevented him from running the country.

But five years later, he agreed to run and was elected virtually unobstructed with 74 percent of the vote.

The other six contenders quit the election 24 hours before the ballots were cast, saying the presidential vote was rigged.

Ending the war

Bouteflika spent his first years as president trying to end the civil war, capping his effort with the 2005 Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation, which granted amnesty to armed groups.

Bouteflika then set out to get the country out of diplomatic isolation and kick start its stagnant economy.

High oil prices between 2004 and 2014 allowed the president to invest heavily in building the country’s infrastructure, notably the construction of new roads, the completion of a lagging metro project and the construction of Africa’s biggest mosque.

These projects, however, fell short of many people’s expectations and they accused the president’s family and close entourage of benefitting the most from these state-building initiatives.

“Under Bouteflika’s leadership, Algeria wasted a historic chance to develop in all areas of life, politically, economically and socially,” said Hacen Ouali, a journalist at the independent El Watan newspaper.

Though lauded by many for restoring civilian rule over the military, Ouali said the president had gone too far.

“Bouteflika has focused on concentrating all powers in the hands of the president. He spent his time trying to weaken the army and state institutions, various ministries and the national assembly.”

“He has a strong penchant for monarchic modes of governance. The proof is that he’s been in power for 20 years and wants to run again to institute ‘deeper reforms’.”

In 2008, the president changed the constitution to allow him to run for a third term in office. By then, reports of his failing health had already begun circulating but did not cause too much public alarm.

Passing the torch

When the Arab Spring toppled leaders including those of neighbouring Tunisia and Libya in 2011, Bouteflika was able to use the country’s vast oil wealth and the threat of instability to remain in power.

The population received generous subsidies and low-interest loans. Those, combined with the fear of civil strife – the likes of which Algeria had emerged from only a few years before – kept Bouteflika at the helm.

By 2012, it appeared he was ready to step down. “My generation is finished,” he said in a speech. “Our time is over. Our time is over. Our time is over.” But it wasn’t.

Bouteflika would stand again and win the presidency in 2014, despite suffering a stroke a year earlier.

On February 22, he announced he would run for a fifth term as president, but the decision backfired in spectacular fashion. Tens of thousands of Algerians took to the streets, calling for him to withdraw his candidacy.

Sensing the popular wave of anger, the president announced he would not run, but the protests continued regardless, with those on the streets calling for the whole ruling establishment to quit.

The popular pressure eventually led to Bouteflika submitting his resignation, effective immediately, on April 2.

“My intention … is to contribute to calming down the souls and minds of the citizens so that they can collectively take Algeria to the better future they aspire to,” he wrote.