Pirate or hero? Raffles bicentennial fuels Singapore debate

Singapore – A pristine white statue of a man in Western clothes, arms folded with the air of a conquering hero, stands on the banks of the Singapore River at the site where he is believed to have landed exactly 200 years ago on Monday.

The statue is of Sir Stamford Raffles, who cut a slippery deal with the locals in what was then known as “Singapura” to claim the island as a port for Britain’s East India Company.

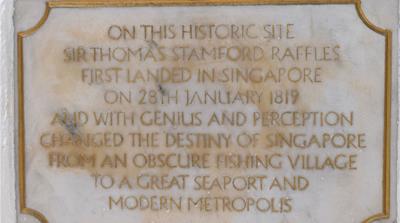

Beneath it, a plaque pays tribute to his “genius and perception” and the way in which he “changed the destiny of Singapore from an obscure fishing village to a great seaport and modern metropolis”.

These days, the statue is popular with shutterbugs, but not everyone looks with pride on the memory of the white settler who brought the forces of imperial domination to an island that would soon be called by its Anglicised name, Singapore.

|

| The dedication at the statue marking Stamford Raffles’s arrival in Singapore 200 years ago [Tom Benner/Al Jazeera] |

“Colonialism did bring trade, laws and infrastructure – for the prosperity of the British. For many of our forebears, it also marked poverty, pain and humiliation,” columnist Tee Zhuo wrote recently in the Straits Times.

“Few nations would fondly remember, much less glorify a former oppressor,” he added.

Nevertheless, on Monday the tiny Southeast Asian nation kicks off a year of commemorations to mark the bicentennial of Raffles’s arrival and what has long been portrayed as the founding of modern-day Singapore.

Many on the tropical island with its diverse ethnic Chinese, Malay and Indian population bristle at the notion that they are celebrating the country’s colonial subjugation and exploitation.

‘Happy place’

Some harbour conflicting feelings over the British imperialists who they say ran roughshod over the locals until they reluctantly agreed to leave in the years leading up to Singapore’s independence in the 1960s.

While art student Goh Hui Ying has heard elders criticise Raffles as a “legal pirate”, she reflects a prevailing view that by creating a free port – without duties or taxes, midway between India and China – Raffles laid the foundation for what is now one of the richest cities in the world.

“I grew up accepting that the British and the East India Company helped us to get started,” said Goh, 32.

Others, meanwhile, are proud of Raffles’ legacy.

“Colonialism is one part. But what we gain today is a beautiful country, a peaceful life, a happy place,” said Sundren Moorthi, 68, a retired police officer, as he strode by the statue with friends.

But Hazirah Helmy, 22, a history student, says it is important to question the traditional view of Raffles as a beneficent saviour, noting that when he landed in Singapore, Raffles exploited a succession dispute among the local Malay rulers to cut a deal that allowed the British to establish a trading post.

“We have to reconsider what his legacy means,” she said. “It’s not been questioned, how we think about our colonial history. The picture has been oversimplified, the idea that he came and he imposed order.”

Bicentennial organisers stress that Raffles’s arrival was a “turning point” in a longer local history that goes back some seven centuries.

“In these 700 years, we went from being a place with a geographically strategic location, to a nation and people with unique characteristics,” they wrote.

‘Unethical and corrupt’

Raffles’s legacy was to bolster trade and shipping with what Britain considered the Far East. Before his arrival in Singapore, Raffles engineered a violent 1812 overthrow of Yogyakarta, the Javanese cultural capital, in what is seen by historians today as an orgy of looting and sacking.

That incident was detailed in Raffles and the British Invasion of Java, a book by historian Tim Hannigan.

“Colonialism was always inherently, fundamentally, structurally unethical and corrupt, even in its supposedly most ‘enlightened’ manifestations,” Hannigan told Al Jazeera. “A proper inspection of Raffles’s record in Southeast Asia makes it plain that any claims made for his own enlightenment and benignity are shaky, to say the least.”

|

| The statue of Sir Stamford Raffles is painted to blend into the buildings of the central business district as part of the bicentennial commemorations [Edgar Su/Reuters] |

Plans for the 2019 bicentennial include a slew of events, museum exhibits, festivals and talks.

A publicity stunt kicked things off earlier this month: the statue at the Raffles Landing Site was partially covered for several days in dark grey paint to create the impression it was “disappearing” into the backdrop of the financial district’s skyscrapers.

The Singapore Bicentennial Office said in a statement: “This optical illusion on the Sir Stamford Raffles statue is … an opportunity to engage Singaporeans in an open dialogue on the arrival of the British, and the contributions of those who came before and after.”

Following that, four additional statues were placed nearby to represent other key historical figures from the region.

Still, many remained sceptical.

“Raffles landing marked the start of colonisation of Singapore,” one Facebook user wrote on the Bicentennial’s official page on the social network.

“The appropriate commemoration is to observe a minute of silence just like how WW2 is being commemorated. To have any activity that is celebratory in nature is inappropriate and a disservice to Singapore pioneers who fought for Singapore independence.”

Another user added: “Don’t understand to why we celebrate colonialism … where local population been curtail of their freedom …. paying tribute and homage to oppressor…??? Maybe that the intention … to support oppression without question… blind obedient!”

‘A thorny issue’

Local academics insist the bicentennial has been successfully framed as a commemoration of history, not a celebration of colonialism.

“The organisers have been careful to emphasise that the events are not intended to celebrate the glories of colonialism through rose-tinted interpretations of the history of the past 200 years,” Professor Tan Tai Yong, president of Yale-NUS College and a member of the bicentennial advisory panel wrote in the local media.

“They have also found it necessary to accept that Singapore has a history that far preceded the arrival of the British.”

Speaking to Al Jazeera, Ngoei Wen-Qing, assistant professor of history at Nanyang Technological University, said organisers understood “that this is a thorny issue and don’t treat the bicentennial as a celebration of Singapore’s colonial heritage, but as an opportunity to inspire a conversation about Singapore’s history”.

“They see it as a chance to rethink British colonialism’s entry into Singapore within a much longer timeline.”

|

|

Singapore has long embraced its colonial past and the name ‘Raffles’ adorns schools, businesses and streets. Raffles Place, the centre of the city’s financial district, in 1968. [File/AP Photo] |

On achieving independence, former British colonies such as India and neighbouring Malaysia moved to replace the anglicised names the British occupiers left behind.

Not so Singapore. It has kept the markings of its colonial past. English remains an official language, and British-sounding place names such as Victoria Street and Queenstown are still in use. The city-state is filled with streets, schools, hospitals and businesses named Stamford or Raffles.

With that historical precedent, many take the view that the bicentennial is a national teaching moment. That tone was set by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, whose People’s Action Party (PAP) has run Singapore since it left Malaysia and became independent in 1965.

“Had Raffles not landed, Singapore might not have become a unique spot in Southeast Asia, quite different from the islands in the archipelago around us, or the states in the Malayan peninsula. But because of Raffles, Singapore became a British colony, a free port, and a modern city,” Lee said in announcing plans for the bicentennial.

Kenneth Paul Tan, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, noted that the colonial narrative is useful for modern, self-governing Singapore.

“History textbooks often present the colonial government not as brutal, oppressive, and exploitative, but as incompetent and ineffective,” Tan told Al Jazeera. “This opens the way for the PAP government to be lauded, in contrast, as heroic in its efforts to transform Singapore ‘from third-world to first’, which has become a popular slogan.”

But given the unease about the bicentennial, and unlike the joyous celebrations around the 50th anniversary of Singapore as an independent nation in 2015, the ever-pragmatic PAP is unlikely to use the festivities as a rallying point for general elections later that could take place as early as this year.