Lewisham, London 1977: Notes on fighting fascism

London, England – “It was the only time in my life I thought I’d probably die. I couldn’t breathe,” says 71-year-old Balwinder Singh Rana.

He recalls the mass of bodies pressed together as police separated anti-fascist protesters from 500 National Front marchers gathered at the bottom of Clifton Rise in the South-East London borough of Lewisham.

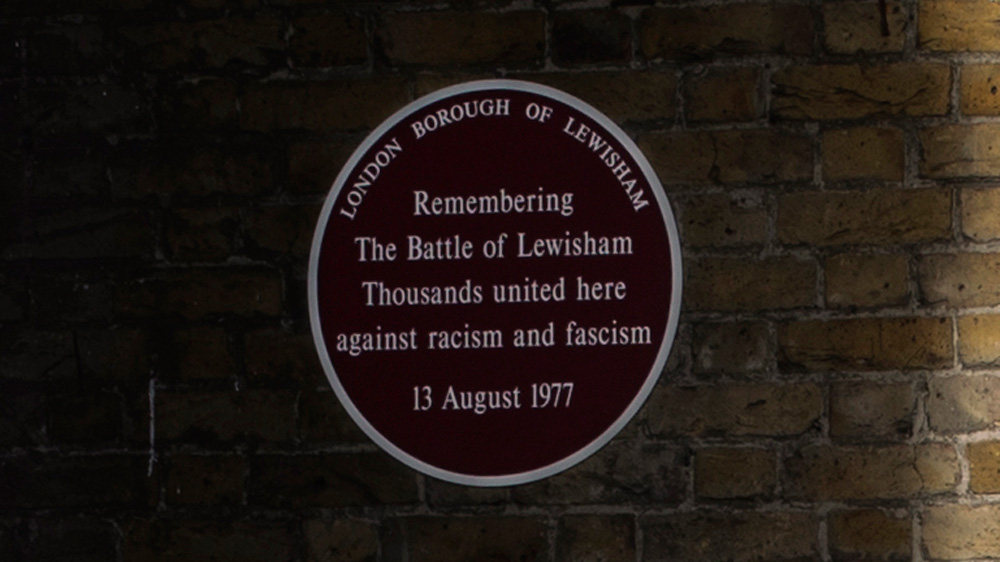

On the concrete wall above him, a small maroon plaque reads:

Remembering

The Battle of Lewisham

Thousands united here

against racism and fascism

13 August 1977

It’s an October afternoon: bright sun and bare trees. Across the street, skaters practice kickflips. Midday traffic hisses by. An elderly woman rests on a set of sculpted concrete seats, her wheeled grocery bag plastered with a Jamaican flag.

But on the day memorialised, the area became a rallying point for the far-right National Front, as people attempted to march through New Cross and Lewisham, ostensibly to protest against a spate of muggings police had attributed to members of the local black population. In response, thousands of anti-fascist protesters rallied in nearby Ladywell Fields.

Rana, a broad, heavyset man with pitch-dark eyes, immigrated to England from India with his family when he was 16. He’s been an anti-fascist his entire adult life, founding Britain’s first Indian youth organisation, The Indian Youth Federation, in 1969 before joining the Anti-Nazi League in 1977.

Strolling these streets, he begins to recount the events of that day.

|

| A memorial plaque in Clifton Rise remembers the events of August 13, 1977 [James Rippingale/Al Jazeera] |

The Battle of Lewisham

It was 11:30am when he and six friends arrived at Ladywell Fields, joining the thousands of anti-fascist protesters already gathered there.

Two separate umbrella groups planned to oppose the National Front march. The All Lewisham Campaign Against Racism and Fascism (ALCARAF), whose appeal to the British High Court to ban the march had been rejected, favoured a peaceful demonstration. The Anti Racist/Anti-Fascist Co-ordinating Committee (ARAFCC) and Socialist Workers Party (SWP) sought to blockade the fascists who’d amassed, under heavy police escort, on nearby Achilles Street.

“One of my comrades from the SWP approached me and gave me a couple of flares which I wrapped up in a newspaper and hid in my belt,” recalls Rana. “He asked me to take a dozen people quietly and make our way here,” he adds, gesturing towards Clifton Rise, now awash with pigeons.

“Then we noticed hundreds of other people were trying to do the same.”

As protesters moved along Achilles Street, police horses and riot officers blocked roads. Clashes began almost immediately. Orange smoke bombs snaked through the crowds. Police forced protesters back onto New Cross Road, clearing a path for the National Front’s march and forming three protective lines either side.

“We let the police pass, we let the [National Front] honour guard pass and when they got to about here,” he says, motioning to a space on Pagnell Street, “we started chucking everything we could. Rocks, bottles, flares …”

|

| New Cross Road, the site of clashes between anti-fascist protesters and supporters of the far-right National Front in 1977 [James Rippingale/Al Jazeera] |

Several of the adjacent houses were derelict. Antifascists concealed on the upper floors and behind garden walls threw bricks at the marchers. Rana chuckles to himself as he recalls members of the National Front cowering in doorways.

In central Lewisham, another group of protesters had amassed, blocking the National Front’s finish line. Unable to proceed they held a brief rally in a car park on Cressingham Road and were escorted swiftly back to Lewisham station.

“We thought we’d won … it was fantastic,” says Rana. “People were so happy. We’d beaten the National Front!”

New police tactics – and a blow to the National Front

But around half an hour later, police equipped with riot shields and batons descended upon the protesters.

“People who were sitting in their own homes were suddenly involved – young or old. People who’d been watching TV. They came out … I even saw some black old ladies from upstairs windows throwing cauliflowers at the police.”

“Now it had become a real community fight.”

The photographs taken that day show bedlam and rage. A black teenager in a police chokehold. Helmets, batons and smoke. Vans with windows smashed in and protesters scrambling atop street signs.

According to researchers at nearby Goldsmiths University, 2,500 police were dispatched with 214 arrests and at least 111 people were injured, including 56 police officers. Seven police coaches were damaged. It was also the first documented use of police riot shields in the UK outside of Northern Ireland.

|

| August 1977: An injured policeman is carried from Lewisham riot by colleagues [Getty Images] |

“Although police attacked us and we were fighting back, even then everyone felt so happy. We were exhilarated that we’d beaten the fascists,” says Rana, ambling up a tree-lined street off New Cross Road.

The day dealt a heavy blow to the National Front.

The year before, it had secured 44.5 percent of the vote, alongside a breakaway faction called the National Party, during a local by-election in Deptford – a result that wasn’t sufficient to beat the Labour Party but which did push the Conservatives into fourth place.

Now, they’d been forcibly ejected from an area in which they believed they had support. Later, Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher would capitalise on paranoia over immigration to draw many of its members towards her party.

We thought we’d won … it was fantastic. People were so happy. We’d beaten the National Front!

Balwinder Singh Rana

A path towards activism

Sitting at a small cafe, Rana explains his own path toward activism.

“Up to the age of 14 I had never seen a white person. I had never suffered from any discrimination. So when I came to this country at the age of 16 it was quite a big shock.”

Rana’s family relocated from Punjab to Gravesend, a small town 21 miles downriver. On his brother’s advice, he began looking for factory work.

“I didn’t speak much English and the boss of the factory was next to a barrier … I went up to this man and I said to him ‘job, please,’ because that’s all I could speak. And he said to me “your people are not allowed to cross this barrier’.”

His brother told him not to worry. This was normal.

“I noticed that a lot of the older people were accepting it because they’d sold everything they had in India to come over here and many of them had families over there and they were quite vulnerable.”

|

| Seventy-one-year-old Balwinder Singh Rana arrived in the UK from India when he was 16 years old. He has been an anti-fascist his entire adult life [James Rippingale/Al Jazeera] |

Over the next five years, as Rana worked different factory jobs, the casual racism remained a constant.

“For them, it was just a bit of a joke. If you argued against them they’d stop. One or two I actually became friends with … You didn’t feel there was something behind it – that they were part of an organisation or anything.”

The Indian Youth Federation

In 1969, Rana set up the Indian Youth Federation while studying for his A-Levels at Gravesend College. His motivation was Enoch Powell’s 1968 Rivers of Blood speech, which ferociously declaimed the “preventable evils” of immigration, spawning a wave of racist attacks across England.

“We came out of a pub and three or four [men] came and abused us verbally. My brother’s two friends were from India. They were fairly big men and college educated. But they didn’t want to fight back. I wanted to fight back.

“From that moment on I thought ‘I’m not going to accept this’.”

Soon, the Indian Youth Federation grew in numbers and confidence.

“There was this pub we knew that didn’t serve Indians. We met somewhere and we marched down to this pub. There were 50 of us. I went to the bar and I said ’50 pints of lager please’,” he says laughing. “Before, they’d say ‘go away’ or if people would go in they wouldn’t serve them … Now, they were rushing around like crazy.

“When the National Front started marching, that was different. That was something much deeper. There was a philosophy behind it.”

|

| Three months before the National Front marched through Lewisham, it had staged a march in the predominantly black area of Wood Green. That had been a departure from the Asian areas it typically targeted and had helped to unite black and Asian Londoners in opposition to the far right [James Rippingale/Al Jazeera] |

‘Defeating fascism together’

Formed in 1967 by A K Chesterton, the National Front gained momentum in 1972 after a large-scale merger between British nationalist groups.

Three months prior to Lewisham, they marched through the predominantly black Wood Green, a departure from the Asian areas initially targeted. This helped galvanise the black community against them.

“That gave us Asians real encouragement. Now, we’re together. Now, we can defeat fascism.”

After the Battle of Lewisham, Rana worked full time for the Anti-Nazi League.

Although the day is seen as a victory, he says little has changed. To his knowledge, 216 marches by far-right groups like the English Defence League, Britain First, National Action and Generational Identity took place in 2018.

“Marching is very, very important for fascists,” says Rana. “When they march in large numbers, even a small worm feels like a dragon.”

|

| Anti-fascist Rana remembers the day in 1977 when Lewisham took on the far right [James Rippingale/Al Jazeera] |

According to his experience, identifying the hardcore members of such groups and separating them from the casuals swept in by rhetoric is key. As is paying attention to urban landscapes: small stickers or slogans plastered on walls and lampposts which ordinarily go unnoticed.

“Use social media as much as you can, but opposing them on the streets is important. Otherwise, they gain the streets … You always have to take small steps from the beginning and start to take action in your local area: start protesting and start organising.”

Today, Lewisham bears little resemblance to the scenes of August 13, 1977.

But on October 13, 2018, Rana was in Central London with the Anti-Nazi League, protesting against a 1,500-strong march by the Democratic Football Lads Alliance (DFLA) against “returning jihadists” and “thousands of Awol migrants,” according to their Facebook page.

“That’s the first time I’d seen 1,500 fascists,” he says, shocked.

“It’s important that people in communities know what’s happening and realise it’s not something that happened in the past. It’s happening right now.”

Across Europe, the far right is on the rise and it has some of the continent’s most diverse communities in its crosshairs.

To the far right, these neighbourhoods are ‘no-go zones’ that challenge their notion of what it means to be European.

To those who live in them, they are Europe. Watch them tell their stories in This is Europe.